By Paloma Sisneros-Lobato, Food and Agriculture Senior Policy Associate

Each year SPUR tracks how Oakland and San Francisco allocate the revenues from soda taxes, which are meant to reduce the harms of soda consumption. Specifically, we’ve looked at how well each city’s budget reflects equity-focused recommendations aimed at keeping the spending aligned with the taxes’ stated purpose. This year, we added a new dimension to our analysis by asking whether the two taxes reflect key principles of good government. We found that their implementation could be more transparent and efficient.

Sugar-sweetened drinks are the single-largest source of sugar for American adults and children, and research shows that they are associated with many diet-related diseases, including diabetes. Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes are one tool that policy makers around the country have been exploring to try to reduce soda consumption and fund healthy eating and active living initiatives in their cities. The Bay Area has been a leader in this movement: Berkeley passed the nation’s first SSB tax in 2014; Oakland and San Francisco residents voted to implement SSB taxes two years later.

To increase the chances that they would pass at the ballot, the Oakland and San Francisco soda taxes were designed as general taxes rather than specific taxes, which means that they have no specified funding allocations. (Compared with specific taxes, which require a 66% affirmative vote, general taxes require only a 50% yes vote.) The structure of general taxes required Oakland and San Francisco to establish advisory boards to make recommendations about how SSB revenue should be spent each year. These boards have no decision-making power. The final call on the budget is left to city leaders — the mayor and members of either the city council or the board of supervisors — who are not required to adopt the recommendations.

Every year, SPUR analyzes how San Francisco and Oakland are allocating SSB tax revenue and whether the advisory boards’ recommendations are followed. This year, we took our research one step further, assessing whether implementation of these SSB taxes reflect two key principles of good government: (1) transparency and (2) effectiveness. In short, our goal is to understand whether Oakland and San Francisco are implementing SSB taxes in an equitable way that benefits the low-income and primarily communities of color most burdened by the SSB industry.

Oakland

Transparency

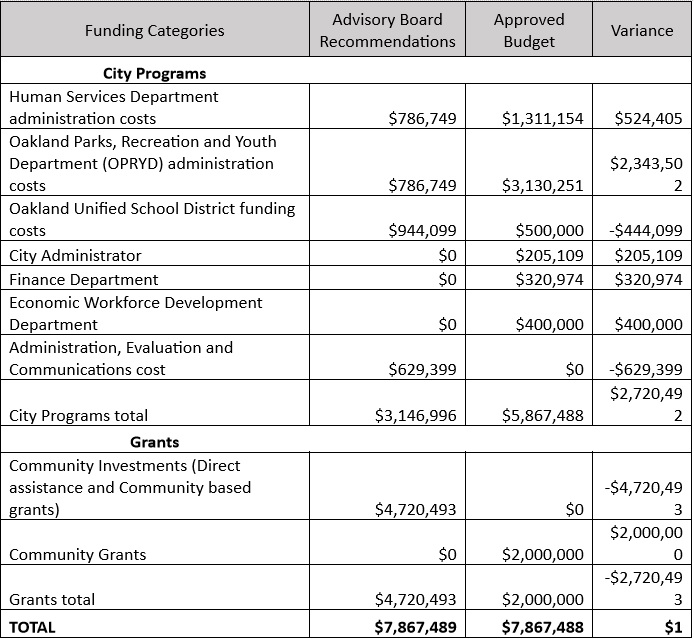

To assess the SSB budget in Oakland, we first reached out to the SSB Community Advisory Board to obtain the approved budget and annual recommendations, information not published directly on the board’s website. We then used these figures to highlight the differences between the advisory board’s recommendations and the final budget.

To track the spending and allocations, SPUR used the city’s live database with the most up-to-date budget figures for the City of Oakland. Although the database is intended to be a transparency tool, it proved challenging to navigate. Moreover, many of its labels do not match those of other city budget documents, including the Comparison of Oakland Advisory Board Recommendations and Final Budget that we obtained from the Community Advisory Board.

Effectiveness

When we compared the Community Advisory Board’s recommendations to the final approved budget, we found that the Oakland mayor and city council did not take the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Community Advisory Board’s recommendations into account in any meaningful way. The advisory board proposed that the Oakland budget allocate 60% of the Fiscal Year 2022–23 revenue to community-based grants. The approved budget allocates just 25% for that purpose. Although the advisory board called out this disparity to the mayor and city council in numerous letters, no changes to the final budget resulted.

Comparison of Oakland Advisory Board Spending Recommendations and Final Budget FY22–23

Oakland’s city budget has faced challenges for years, threatening many city services with elimination or underfunding. The spending allocation from the SSB tax suggests that Oakland is using the revenue from this tax to fill voids in the city’s General Fund rather than to support programming specifically targeted at improving healthy living in line with the tax’s original intent. The divergence of the city’s revenue allocation from the advisory board’s recommendations reflects ineffective implementation of the SSB tax.

San Francisco

Transparency

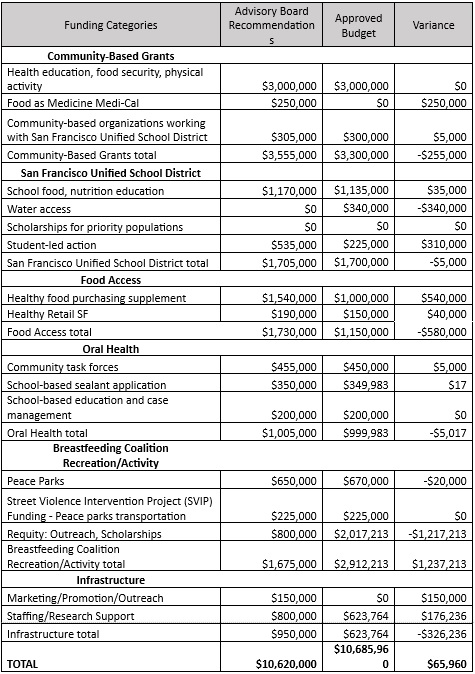

To assess the budget in San Francisco, SPUR used the mayoral budget and the Sugary Drinks Distributor Tax Advisory Committee (SDDTAC) recommendation comparison document that is published on the SDDTAC website. We calculated the difference between the recommendations and the approved budget. Overall, information about the recommendations and the budget is easy to find under resources on the committee’s website.

Effectiveness

The SDDTAC makes recommendations for six major funding categories. In general, the City and County of San Francisco FY22–23 budget loosely matches those recommendations. The allocations diverge from the recommendations in a few notable respects.

First, the budget allocated no funds to Food as Medicine Medi-Cal. These funds would have provided one-time infrastructure and capacity-building grants for community-based organizations that already provide medically supportive food and nutrition interventions. These organizations would have used the grants to contract with health plans to take advantage of Medicaid funding available through CalAIM, California’s current Medicaid waiver.

Second, the city did not fully fund healthy food purchasing supplements. These supplements provide support for programs that help low-income San Franciscans buy healthy foods — programs directly aligned with the goals of the SSB tax.

Third, the city allocated significantly more money than recommended to the city’s free Requity program, which is operated through the Recreation and Parks Department. The funds for outreach and scholarships and for equity building in city recreation programming are meant to improve the health and wellness of San Francisco youth. This programming is certainly beneficial. But the large percentage of the SSB tax revenue allocated for it is concerning because funding from SSB tax revenue should not supplant funding for programs traditionally supported through the General Fund.

Comparison of SDDTAC’s Spending Recommendations and San Francisco Mayor’s Proposed Soda Tax Allocations FY22–23

Bay Area SSB Taxes Can Set a Precedent for a Statewide SSB Tax

Researchers, government officials and advocates continue to look to Oakland and San Francisco as exemplars of soda tax campaigns. Because any potential future statewide SSB tax would likely pursue goals similar to those of the Oakland and San Francisco SSB taxes, it’s important to track how well tax administration reflects good government principles and how revenue allocation is impacting targeted communities. SPUR recommends that both the Oakland and San Francisco mayors better align the final budget allocation of SSB taxes with their advisory board’s recommendations. The advisory boards dedicate significant time and resources to identifying recommendations aimed at equitable distribution of funds, and their recommendations should be followed more closely. SPUR will continue to compare the Oakland and San Francisco budgets with advisory board recommendations to assess whether the allocation of SSB revenue aligns with the goals of the SSB taxes.